BLI's 100 Years....100 Duels Numbers 79 to 70

- bigleagueinvestigations

- Jan 21, 2024

- 36 min read

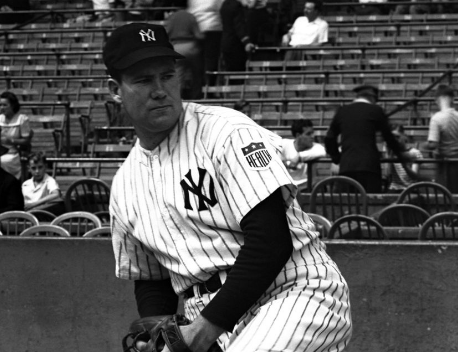

Number 79- Tiny Bonham (NYY) vs. Allie Reynolds (CLE), August 19, 1943

Right-handed power pitcher Allie Reynolds appears on our 100 Years, 100 Duels list three times, the first being his duel versus the New York Yankees’ Ernie “Tiny” Bonham which occurred on August 19, 1943. Three years after his duel with Bonham Reynolds would be acquired by the Yankees from the Indians in exchange for six-time all-star second baseman, Joe Gordon, who incidentally also played a prominent role in this game.

In 1943 Reynolds was drawing comparisons to Indian great, Bob Feller. Feller though was not with the Indians in ‘43. Instead he was serving his second year of what turned out to be a total of three years in the military. In ’42, their first season without Feller, Cleveland posted a 75-79 won/lost record. In ’43, the Indians improved to 82-71 thanks in large part to the reemergence of veteran pitchers Al Smith and Vern Kennedy as well as the emergence of Allie Reynolds.

In the year prior Smith and Kennedy combined for just 14 wins and had lost a collective 23 games. Nevertheless, despite their poor records Cleveland player-manager, Lou Boudreau, chose to open the season with both pitchers in his starting rotation rather than inserting one his highly touted youngsters: Mike Naymick, Paul Calvert, Ray Poat or Allie Reynolds. Eventually though Reynolds would earn himself a spot in the rotation.

After a couple of mediocre doubleheader spot starts in June, Reynolds fired a complete game three-hit shutout versus the Yankees on July 2. He followed up that start with a complete game victory over the Washington Senators. In the month of July Reynolds started a total of seven games, completing four of them. He was 3-2 in said starts with a tidy 2.13 ERA and had struck out 44 batters in 55 innings. However, he had also walked 28.

In his first start in August, Reynolds fired another complete game three-hit shutout

versus the St. Louis Browns. He struck out nine batters and walked three. It was this start versus the Browns that, in the eyes of Cleveland manager, Lou Boudreau, signaled the flame-throwing rookie’s arrival. What had impressed Boudreau most was the fact that Reynolds hadn’t simply relied on his fastball as he had done when he blanked the Yankees just weeks before. In that start Reynolds had thrown only four curveballs the entire game. In this start against the Browns though, Reynolds utilized his curve much more frequently and had the confidence to use it at any time including at one of the most critical junctures of the game.

Clinging to just a one-run lead with one out in the ninth, Reynolds was set to face the Browns’ all-star clean-up hitter, Chet Laabs. Reynolds had previously struck out Laabs twice. In this at-bat Laabs had worked Reynolds to a full count. With the count 3-and-2 Indians’ catcher, Buddy Rosar, called for the curve. Reynolds acknowledged Rosar’s sign and then proceeded to break-off a fantastic bender that froze Laabs to strike him out looking. “That pitch,” Boudreau commented after the game, “proved Reynolds has complete confidence in himself and his catcher. Buddy Rosar called for the curve and Reynolds didn’t question the sign (36).”

Besides a fastball and curveball, Reynolds also possessed a change-up and an overhand slider. He had “three deliveries- overhand, three-quarters and sidearm. The latter delivery reserved exclusively for right-handed hitters…left-handed batters got his overhand and three-quarters deliveries (37).”

After beating the Browns Reynolds had begun to garner national attention. The media pointed to his seven strikeouts per nine innings which was higher than notable AL strikeout artists such as Hal Newhouser, Tommy Bridges, Virgil Trucks and Bobo Newsom. “Allie Reynolds, the Cleveland Indians’ husky right-hander, is making a belated bid for recognition as the American League’s outstanding rookie pitcher of the year…the quarter-blooded Creek with the tantalizing fastball has been regarded by veteran observers as the Redskin recruit most likely to succeed in 1943…and is one of the league’s most proficient strikeout artists…he is considered the best mound prospect on the Cleveland club since Bob Feller (38),” the Associated Press wrote.

Indeed. Reynolds, an Oklahoma A&M graduate that had starred in both track and field as well as football (Reynolds had rejected an offer from the NFL’s New York Giants after graduating) and who had resisted the idea of being converted to an outfielder was now considered to be one of the brightest up and coming pitchers in the game. A 13-inning gutsy performance in a rematch versus the powerful Yankees would cement those sentiments.

The ’43 Yankees were without notable star players Joe DiMaggio, Tommy Henrich and Phil Rizzuto due to the war. Still though the Yankees possessed a potent line-up led by their slugging left fielder, Charlie Keller, the aforementioned Joe Gordon and veteran catcher Bill Dickey. Indeed, the eventual 1943 World Champions had once again led the AL in runs scored and homeruns.

Led by 20-game winner and AL MVP Spud Chandler, the ’43 Yankees had also allowed the least runs in the American League. Tiny Bonham posted the next highest win total for the Yankees with 15. Bonham had been called up by the Yanks in August of 1940. At that time Bonham was pitching for the Kansas City Blues, a double-A Yankee affiliate. He made his first career start on August 5, 1940 versus the Boston Red Sox. Bonham went the distance but lost 4-1. Two starts later Bonham lasted just two and a third innings as Boston clobbered New York at Yankee Stadium 11-1, dropping the Yankees to ten games behind the AL leading Cleveland Indians.

However, after the drubbing Bonham had received at the hands of the Red Sox, the six-foot-two 215 pound rookie right-hander reeled off an 8-1 record with a sparkling 1.46 ERA, including a complete game win versus Bob Feller and the Cleveland Indians that knocked Cleveland out of top spot in the AL and got the Yankees within one game of the first-place Detroit Tigers. The ‘40 Yankees ultimately fell short of capturing their fifth consecutive AL Pennant but were well-positioned for 1941 with a full year of Bonham in the rotation.

Unfortunately for the Yankees, Bonham was limited to just 14 starts in ’41 due to a back injury. Nevertheless the Yankees won the AL Pennant and then the World Series in five games over the Brooklyn Dodgers. Bonham twirled a four-hit, complete-game gem in the Game 5 clincher. Completely healthy in ’42 Bonham was able to post a 21-5 record and led the AL in both complete games (22) and shutouts (6).

By the time the Yankees had arrived in Cleveland to face Allie Reynolds and the Indians, Bonham had arguably established himself as the Yankees’ best starting pitcher over the last 3+ seasons. Indeed, going back to the day he made his first career start in ‘40, Bonham led the Yankees in wins (50); innings pitched (613.1) and ERA (2.36). Heading into Cleveland he was 11-5 with a 2.29 ERA and ranked as baseball’s number five pitcher.

The Indians had defeated Bonham 3-1 in the first game of a May 23 doubleheader. In the second game of the twin-bill the Indians beat the Yanks’ Spud Chandler 5-2. The doubleheader sweep of the Yankees put the Indians in sole possession of first place in the AL which would be the first and only time Cleveland would lead the AL that season.

The Indians would sweep the Yankees in another doubleheader in Cleveland on August 18, one day before the Reynolds/Bonham duel. Despite the sweep the Indians were still a distant nine games behind the first place Yankees. Interestingly the August 18 doubleheader was played at League Park as opposed to the massive 70,000+ seat Cleveland Municipal Stadium which was the site of the May 23 doubleheader.

In the years 1937 to 1946 the Indians played their home games at both League Park and Municipal Stadium. Generally speaking, League Park was the Indians’ home venue for ordinary weekday games with the much larger capacity-sized Municipal Stadium reserved for weekend games as well as holidays or when the star-studded Yankees came to town. The purpose of having the two home parks was to maximize revenue and limit expenditures.

Besides the increased attendance figures that Municipal Stadium had afforded the Indians, the ballpark had also benefited Cleveland pitching given its spacious outfield dimensions which suppressed power and run production as opposed to the hitter-friendly League Park. The contrast in how each park played provided the Indians with an opportunity to be more strategic as to which home games they’d schedule at which ballpark. Given that the Indians had only one season in which they had a losing home record in the years they were playing at both parks suggests that the way in which Cleveland set their home schedule created a distinct home field advantage.

After sweeping the Yankees on August 18 at League Park, the Indians scheduled the Thursday, August 19 tilt between Reynolds and Bonham to be played at Municipal Stadium in anticipation of a large crowd. Sure enough the game drew 36,000+ fans, the largest Cleveland home crowd of the year and Reynolds and Bonham did not disappoint. The fans were treated to a classic pitcher’s duel with Municipal Stadium playing an important supporting role to Reynolds’ and Bonham’s leading roles.

The game began under rather inauspicious circumstances. Halfway thru the playing of the national anthem, “the record playing the Star Spangled Banner cracked and stopped midway through the anthem (39),”a definite a sign of things to come.

After Reynolds set the Yankees down in order in the first inning, he opened the second by walking the Yanks’ slugging left fielder Charlie Keller. Reynolds then struck out Nick Etten for the first out of the inning. Up next for New York was its number six hitter, Ken Sears. As Sears walked to the plate a semi-blackout in Municipal Stadium ensued. Indeed, “A power-plant breakdown, blacking out four of the seven huge batteries of lights atop the stands halted play (40).”

Along with the candelabras being short-circuited the stadium’s public address system was also knocked out which caused even more confusion. Sensing that it would take time to repair the lighting both teams had agreed to waive the rule prohibiting the beginning of an inning after 11:55 PM. After more than a one hour delay stadium electricians informed home plate umpire, Bill Summers that they had yet to resolve the issue. Summers then consulted with managers Lou Boudreau and Joe McCarthy. Both managers ultimately agreed to play the game “under a single row of lights along the roof used for football and amateur baseball games (41),” meaning that the rest of the game would be played with the “entire left-side of the roof and one of the right-field towers still in darkness (42).”

Despite the lights being out, when play had finally resumed, there was still plenty of electricity in the stadium thanks to Reynolds and Bonham. Reynolds had ended the second inning by first retiring Sears on a groundout and then Joe Gordon on a fly ball hit to left field. In the bottom of the second, after surrendering a one-out single, Tiny Bonham threw a high and hard inside pitch to Lou Boudreau, knocking Boudreau off his feet. Two batters later Bonham threw another hard and tight pitch, this time at Reynolds. After almost being drilled by Bonham, Reynolds “shouted at the Yank pitcher (43).” Bonham, willing to confront Reynolds, walked down off the mound and directly at him. To avoid a possible brawl, Bill Summer intervened and restored order. The speculation was that Bonham throwing at both player/manager Boudreau and Reynolds was retribution for Reynolds almost hitting Yankee Ken Sears in the top-half of the inning after play had resumed. After the near dust-up Bonham retired Reynolds on a pop-up to first to end the inning.

Given the reduced stadium lighting both Reynolds and Bonham “had been expected to approach a strikeout record with the advantage of pitching under lamplights hardly suited for the best type of baseball (44).” Surprisingly though that did not happen as both pitchers were extremely efficient. In the combined 25 innings Reynolds and Bonham had thrown, a total of 13 strikeouts were recorded and a mere three bases on balls were issued.

The pitchers had been locked in a scoreless duel up until the bottom of the sixth when Indians’ center fielder, Oris Hockett, had led off the inning by way of a single to center. Hockett then advanced to second thanks to a Roy Cullenbine sacrifice bunt. After which Bonham was able to get the dangerous Jeff Heath to fly out to left before Buddy Rosar singled home Hockett to open the scoring and put the Indians ahead 1-0.

Reynolds then retired the Yankees in order in both the seventh and eighth innings, three of the strikeout variety. Bonham also pitched a 1-2-3 eighth inning to keep the Yankees within one run. In the ninth, the high-powered Yankee offense finally got to Reynolds. With one out Yankee right fielder, Bud Metheny, ripped a double down the left-field line.

Reynolds was able to get the Yankees’ next hitter, third baseman Billy Johnson, to hit a comebacker to the mound. Believing he had Metheny trapped between second and third, Reynolds chased the Yankee right fielder back to second rather than electing to get the sure out at first. Reynolds then threw the ball to second in an attempt to get Metheny but threw it too soon. As a result, Metheny broke for third. Lou Boudreau though was able to gun Metheny down at third but the alert Billy Johnson had advanced to second on the play.

With two outs and clinging to a 1-0 lead, Reynolds was set to face the heavy-hitting Charlie Keller. Reynolds had previously walked Keller twice. In their last encounter, Reynolds had Keller fly out to right field. This time though, Keller smacked a single to center to score Johnson and tie the game at one. Reynolds then retired Etten on a fly ball to right to end the inning.

In the bottom-half of the ninth, Bonham had surrendered a two-out single to Indians’ second baseman, Ray Mack, but stranded him after retiring Reynolds on a groundout. After nine complete the game was tied with both Reynolds and Bonham headed for extra innings. Who’d blink first?

In the top-half of the 10th, Reynolds made quick work of the Yankees with another 1-2-3 inning. In the bottom-half of the frame, Bonham allowed a lead-off single but again was able to strand the runner to preserve the tie. In the 11th, Reynolds once again sat the Yankees down in order. Bonham though responded with a 1-2-3 11th inning of his own which included striking out Lou Boudreau for the third time. Boudreau would strike out only 31 times the entire ’43 season and would strike out thrice in a game just three times in his entire career.

In the 12th inning Reynolds and Bonham each surrendered singles but nothing more. Reynolds allowed a two-out single to Nick Etten but retired Ken Sears on a fly ball to right to end the inning. Bonham yielded a one-out Allie Reynolds single but retired him at second on a force prior to having Oris Hockett fly out to center to end the inning.

The 13th inning ended up being the bad luck inning for Reynolds. Joe Gordon led off the frame by lacing a Reynolds offering down the left field line for a double. The next batter up for New York was center fielder Turk Stainback. Stainback had entered the game in the eighth inning to replace Bill Dickey who had pinch hit for Johnny Lindell. Reynolds had struck out Stainback in their previous encounter. This time though Stainback was able to get a hold of a Reynolds pitch and drive it to deep center allowing Gordon to tag up on the play and advance to third after Hockett corralled the fly ball for the first out of the inning.

With the potential winning run now on third, Yankee manager, Joe McCarthy, sent the 35 year-old veteran, Rollie Hemsley, up to pinch-hit for Bonham meaning that Bonham’s day was finally done. The forkball throwing specialist had hurled 12 innings of eight-hit ball, allowed just one run, walked one and struck out six for an 87 Game Score. Moreover, Bonham was still the Yankee pitcher of record. If Hemsley delivered Bonham would be in a position to win the contest.

Sure enough Hemsley was able to connect on a Reynolds pitch sending, in what the Associated Press reported a “long fly” to center. Hockett made the out for the Indians but Gordon tagged up on the play to score the go ahead run. The Yankees were now up 2-1 with Tiny Bonham set to win his 12th game of the year, that is if the Yankee bullpen was able to shut the door in the 13th.

Having thrown 4.2 innings the day prior, the Yankees’ regular closer, Johnny Murphy, who had led the AL in saves four of the last six seasons was unavailable on this day. Instead of Murphy, Yankee manager, Joe McCarthy, called upon his rookie right-hander, Charlie “Butch” Wensloff to close out the game. Interestingly, Wensloff was not a relief pitcher. In fact, Wensloff began the season in the Yankee rotation, the first rookie pitcher to begin his Yankee career in the starting rotation since Johnny Allen had done so back in 1932.

Wensloff, who ended up walking just 11 batters in over 223 innings pitched in ’43 began the 13th inning uncharacteristically by issuing a leadoff walk to Roy Cullenbine. However, Wensloff was quick to recover. He retired the next three Indians in order for his first and only save of his major league career.

Allie Reynolds was tagged with the hard-luck loss. In his 13 innings pitched, Reynolds had given up just six hits and had walked two while striking out seven for a 92 Game Score. The highest Game Score of Reynolds’ career would come two years later versus Nels Potter and the St. Louis Browns. Reynolds’ duel with Potter is ranked just ahead of this duel at 78. Reynolds would win that duel with Potter as well as his duel versus Bob Feller and the Cleveland Indians as a member of the New York Yankees in July of ’51 which appears later on our list.

In terms of Game Score, Bonham’s performance against Reynolds and the Indians was the best of his career. Reoccurring back injuries as well as arm pain limited Bonham to just 14 starts in 1946. Shortly after the season ended, the Yankees dealt Bonham to the Pittsburgh Pirates on October 24, 1946. Bonham was deemed expendable given that two weeks prior the Yankees had acquired Allie Reynolds from the Indians in exchange for Joe Gordon.

Number 72- Steve Trachsel (TBD) vs. Pedro Martinez (BOS) May 6, 2000

On April 8, 1994 Steve Trachsel won the first of what would turn out to be 143 career MLB wins. His opponent on the mound that day was Montreal Expo and future Hall of Famer, Pedro Martinez. Trachsel had shutout the Expos for 7.1 innings, allowing just three hits and one walk while striking out eight before a Montreal home-opening crowd of 47,000 at Olympic Stadium.

With that performance, Trachsel, an eighth round pick out of California State University, had certainly made an impression. Those praising the then Cubs’ rookie right-hander included former major league outfielder and then current Montreal Expos manager, Felipe Alou. “Trachsel reminds me of a young John Smoltz (45),” Alou said after the game. “There’s a lot of resemblance. He’s got a good over-the-top fastball and curve but his splitter is probably better (46).” High praise for Trachsel indeed as Smoltz at the time was a three-time all-star and baseball’s number seven ranked pitcher.

Despite being tagged with the loss, Pedro Martinez had been almost as dominant as Trachsel. The then 22 year-old Dominican had struck out eight and walked just one batter over his six innings of work. The only run Martinez allowed was the result, ironically enough, of a first inning double off the bat of light-hitting Cubs utility infielder, Rey Sanchez.

After allowing the Sanchez double, Martinez proceeded to dominate the Cubs. According to Chicago outfielder, Tuffy Rhodes, who had scored on the Sanchez double, Martinez “was bringing it (47).” Rhodes elaborated further by saying, “We saw Doc Gooden already, but that guy out there today was the best pitcher we’ve faced in a long time (48).”

Martinez’s April 8, 1994 start versus the Cubs was his first as a Montreal Expo. He was originally signed by the Los Angeles Dodgers. However, just a year and a half after Dodgers’ general manager, Fred Claire, stated that he “wouldn’t trade Pedro Martinez, I don’t care what the offer is (49),” Claire dealt Martinez to the Expos in November of 1993 in exchange for second baseman Delino DeShields.

Of course the deal worked out extremely well for Montreal. The ’94 Expos, who had finished the previous season in second place, just three games behind the NL champion Philadelphia Phillies in the NL East, were sitting atop the newly realigned east division with a 74-40 record and well on their way to post season play when the ’94 strike occurred. That year Martinez was 11-5 with a 3.42 ERA.

Over the next three seasons, as the Expos struggled to stay above .500 and hold on to their nucleus of young star-players Martinez excelled, culminating with a 17-8 1997 season in which he led the NL with a microscopic 1.90 ERA to win the first of his three Cy Young Awards.

In November of ’97, almost four years to the day after being traded by the Dodgers to the Expos, Martinez was once again traded, this time to the Boston Red Sox. Martinez, who was reportedly set to make $6 million in the upcoming 1998 season through arbitration and well on his way to becoming a free agent at season’s end, had become too expensive for the cash-strapped Expos to retain, thus the deal was made.

In 1998, Martinez’s first year in Boston, the flame-thrower won 19 games with a 2.89 ERA as Boston improved from a 78-84 record in ’97 to 92-70 and a wild card playoff berth in ‘98. Martinez followed up his stellar 1998 campaign with a brilliant ’99 season, arguably one the greatest seasons ever produced by a pitcher in MLB history. Indeed.

That year Martinez captured the AL’s pitching Triple Crown by leading the league in wins, ERA and strikeouts. Martinez’s 2.07 ERA was 1.37 runs better than runner-up David Cone’s 3.44 ERA and an incredible 2.79 runs better than the league average. His 313 strikeout total led the next best AL total by 113. In capturing the AL Cy Young Award in ’99 by way of an unanimous vote, Martinez had become just the second pitcher in history to win the Cy Young Award in both leagues. Martinez had also received the most first place votes in AL MVP voting that year but was edged out in points by Texas’ Ivan Rodriguez.

Heading into the 2000 season, Martinez was clearly baseball’s number one pitcher and began the campaign the way he finished the ’99 season, by completely dominating the AL. Indeed, by the end of April Martinez was off to a 5-0 start and was almost unhittable. In 35.1 innings pitched he had struck out 50 batters and walked just eight. Opposing hitters were batting just .143 and slugging a miniscule .236 off of Martinez. Moreover, Martinez had given up just five earned runs in his five starts. His next start would come against Steve Trachsel and the 11-18 Tampa Bay Devil Rays.

As much as Martinez’s career had taken off after his start against Trachsel and the Cubs in ’94, Trachsel’s career had been up and down with alternating good and bad years. Trachsel finished his 1994 rookie campaign with a 9-7 record and a very respectable 3.21 ERA, second only to Houston’s Shane Reynolds among NL rookies. He finished fourth in NL rookie of the year voting.

In 1995 Trachsel regressed. His ERA ballooned to 5.15, the highest among Cubs’ starters. Trachsel was also the only Cubs starting pitcher in ’95 to have a losing record thanks in large part to a 2-8 record at Wrigley Field where his ERA was an ugly 6.19. However, the following year Trachsel rebounded.

After being left off of the opening day roster at the beginning of ’96, Trachsel went on to have an all-star season. He was 13-9 with a team best 3.03 ERA amongst Cubs’ starters. Trachsel had also cured whatever had ailed him while pitching at Wrigley as the right-hander went 9-5 at his home park with a sub-3.00 ERA.

In 1997 though, Trachsel once again reversed course. He was 8-12 with a 4.51 ERA. The following year Trachsel improved his ERA slightly to 4.46 but won 15 games thanks to a potent Cubs offense led by NL MVP, Sammy Sosa. In 1999 Trachsel’s ERA rose by more than a full run and his run support declined by about one run. The result: only eight wins and a MLB-leading 18 losses.

Unfortunately for Trachsel those 18 losses were in the year before he was set to hit the free agent market. As a result, he wasn’t signed until late January of 2000 when the Tampa Bay Devil Rays inked Trachsel to a one-year $1 million contract plus incentives. Trachsel, who had originally been slated as Tampa’s number-three starter was named the Devil Rays’ 2000 opening day starter thanks to both Wilson Alvarez and Juan Guzman beginning the season on the disabled list.

It appeared as though the good year/even year trend would continue for Trachsel in 2000 when he opened the season with a seven-inning start versus the Minnesota Twins in which he gave up zero runs, walked zero and struck out seven. However, in his next five starts Trachsel was 0-2 with a lofty 7.76 ERA. Overall, heading into his start versus Pedro Martinez and the Boston Red Sox, Trachsel was 1-2 with a 6.15 ERA. Martinez on the other hand was riding a 13-game winning streak. On paper the Trachsel versus Martinez matchup was a clear mismatch to say the least, something Trachsel was made very well aware of.

“You’ve got Pedro [Saturday May 6]. Good luck (50),” a hotel staffer had reportedly said to Trachsel after the Devil Rays had arrived in Boston that weekend. However, it wasn’t luck that Trachsel would rely on to totally shut down the Boston offense that day. Instead it was variety, as in the variety of different pitches Trachsel threw at Red Sox batters and the location at which he threw them that led to Trachsel pitching the best game of his career. “From my perspective, it just didn’t look like they (Red Sox) knew what he (Trachsel) was going to do to them (51),” Devil Rays catcher John Flaherty reflected after the game. “When they were looking away, he’d pop them in. When they were looking in, he’d throw a good split-finger. He had them off-balance all day (52).”

Pedro Martinez though returned the favor by utilizing a devastating combination of fastballs and change-ups and a wicked curveball for show. “He’s tough. Any pitch, any time (52),” Devil Rays slugger Greg Vaughn commented after the game. “He’s got great command of all his pitches and you can’t sit on his breaking stuff because he throws 95 miles an hour. You set up for the heater and he crosses you up with a change-up (53).”

With both pitchers baffling opposing hitters, the Fenway crowd was treated to a terrific nine inning Trachsel/Martinez duel as batter after batter took their turn in the box only to slowly trek back to their respective dugouts after being completely fooled by an assortment of pitches. Indeed. Trachsel and Martinez combined had fired a total 28 strikeouts, just two shy of the MLB record that was set exactly two years to the day prior by Trachsel’s former Cubs’ teammate, Kerry Wood, and the aforementioned Shayne Reynolds of the Houston Astros.

Seventeen of those 28 strikeouts belonged to Martinez with six coming in the first two innings as the 27 year-old right-hander was mowing down Devil Ray hitters to begin the game. After just five innings and having struck out every Tampa Bay hitter by then, Martinez’s strikeout total stood at 12.

Fortunately for Tampa Trachsel had been practically matching Martinez inning for inning. He hadn’t put up the gaudy strikeout total that Martinez had but he had whiffed six Red Sox in his first five innings including three swinging strikeouts in the first inning.

In the bottom-half of the sixth, after Martinez had retired the Rays in order in the top-half of the inning it appeared as though Trachsel would finally blink. Trachsel had walked Boston first baseman Brian Daubach to lead off the frame. He then struck out outfielder Carl Everett for the first out of the inning. Trachsel followed his strikeout of Everett by inducing a groundball to the first base side off the bat of Red Sox left fielder Troy O’Leary. However, the ball was booted by Rays’ first baseman Fred McGriff. As a result O’Leary was safe at first and Daubach advanced to third.

Trachsel though was able to recover with a much needed strikeout of Red Sox DH, Mike Stanley, and an inning-ending groundout by Boston catcher Jason Varitek. That sixth inning would be the closest the Red Sox would come to scoring a run. Over his last three innings Trachsel was able to mow down the next nine Red Sox in order.

Heading into the top of the eighth inning the game remained deadlocked at zero. Martinez opened the frame by overpowering Rays’ second baseman Miguel Cairo for his next to last strikeout of the game. Martinez then made quick work of Rays’ leadoff hitter, Gerald Williams, by way of a routine 6-3 groundout for the second out of the inning.

Tampa Bay right fielder, Dave Martinez though, kept the inning alive with a seeing-eye single to right. It was the Devil Rays’ first hit off of Pedro since the fifth inning. In that inning Martinez had given up a two-out single to Miguel Cairo. Cairo then proceeded to steal second but Martinez was able to strikeout Gerald Williams to end the inning stranding Cairo at second.

Similarly in the eighth, Martinez once again surrendered a two-out single, this time to Dave Martinez, and once again the Rays attempted to steal second and were successful but barely. With Greg Vaughn at-bat and the count 1-2, Dave Martinez broke for second. Jason Varitek then rifled a throw in an attempt to nail Martinez. Martinez slid to beat the throw but his foot had appeared to come up short of the bag. Nevertheless he was called safe and the Rays had a runner in scoring position. “His foot came up short (53),” Red Sox pitching-coach Joe Kerrigan commented after the game. “The umpires don’t have the benefit of replay and it was a bang-bang play, but he never got to the bag before the tag (54).”

With Dave Martinez running Vaughn had taken the close pitch for a ball and was now in a 2-2 count. The fact that Vaughn had survived at the plate up until this point was surprising. In his previous three at-bats Vaughn had struck out each time on just three pitches. This time though Vaughn would not go quietly. He battled Martinez to a seven-pitch at-bat before lining a single to left-center to score Dave Martinez and put the Rays up 1-0.

The one run was all the Rays would manage against Martinez but it was enough as Trachsel did not give an inch to Red Sox batters over the last two innings. Trachsel fanned three of the last five hitters he faced and retired the last 11 Red Sox in order. Trachsel finished the day having struck out 11 batters and walking just three. The three-hit complete game shutout resulted in an 89 Game Score, the best of Trachsel’s career. He threw a total of 132 pitches, 76 for strikes. “You can’t pitch any better than that unless you’re Pedro…It’s as good as it gets (55),” Devil Rays manager Larry Rothschild said after the game.

Trachsel though had pitched better than Martinez if measured by Game Score. Trachsel’s 89 Game Score was slightly better than Martinez’s 87. Overall Martinez gave up six hits and walked just one to go along with his 17 strikeouts. In doing so Martinez became just the fourth pitcher in MLB history to strike out at least 17 batters in a nine-inning game and lose, joining Hall of Famers Bob Feller, Steve Carlton and Randy Johnson. Of Martinez’s 130 total pitches, 91 were thrown for strikes.

After the game David Martinez stated the obvious, “Steve Trachsel was the MVP today (56).” Indeed.

Of note the Trachsel/Martinez duel is the only duel in our top 100 that occurred in the decade of 2000-2009.

Number 70- Lefty Grove (PHA) vs. Herb Pennock (NYY) July 4, 1925

There are eight duels in the top 100 between Hall of Fame pitchers. The July 4, 1925 duel between Robert “Lefty” Grove and Herb Pennock is ranked the lowest of the eight. The reason being is that Lefty Grove wasn’t the fire-balling with pinpoint control Lefty Grove that won nine AL ERA titles, seven strikeout titles and two Pitching Triple Crowns to boot, not yet anyway. Instead Grove was just a rookie in 1925 that had displayed flashes of brilliance but had struggled mightily with control.

Expectations for Grove were considerably high heading into the 1925 season. He had been purchased by Connie Mack and the Philadelphia Athletics for a staggering $100,600 in October of ’24 from the Baltimore Orioles of the International League. The price paid for Grove was at the time the highest ever paid for a minor leaguer and more than $25,000 greater than the next highest amount. Only the New York Yankees’ purchase of Babe Ruth from the Boston Red Sox in 1919 for approximately $150,000 exceeded Grove’s purchase price.

Grove had been pitching for the Orioles since 1920. With Baltimore Grove racked up 108 wins. He led the International League in strikeouts in ’22, ’23 and ’24. Grove’s career International League strikeout total was reportedly greater than 1,100 (57) in 1,243 innings pitched. In 1924 Grove established a new organized baseball record for strikeouts in a season with 330.

Realizing the chance for a huge payday, Baltimore Orioles owner, Jack Dunn, began to hint in August of ’24 that Grove may be sold at season’s end. Dunn though stipulated that he would be setting the price for Grove’s sale and said price would be substantial i.e. six figures. “I may sell Grove if I get my figure…Grove is getting better all the time and he’ll have a long career…He’s better than Cincinnati’s three southpaws- (Eppa) Rixey, (Rube) Benton and (Carl) Mays- and he’ll go down in history as the best southpaw the game ever knew (58),” Dunn had reasoned.

Just prior to the Orioles winning its sixth consecutive International League pennant in 1924, the team scheduled two exhibition games to be played in early September, one versus the Chicago White Sox and the other against the Philadelphia Athletics. The 26-6 Grove started both games. Against the White Sox Grove yielded just three runs and struck out 14 in a 9-3 victory. Versus the Athletics Grove was even more dominating. The mega-prospect fired a two-hit complete game shutout, fanning 13 batters in the process in a 5-0 win.

Apparently Grove’s performance had thoroughly impressed Connie Mack because approximately five weeks later Mack stunned the baseball world by purchasing Grove for the $100,000 asking price Dunn had demanded. According to Dunn, the Athletics were the only team willing to meet his price for Grove. “I named my price and Connie accepted (59),” Dunn explained. “No one else made an offer for him. It was an outright sale and no other player was involved (60).” Indeed. Lefty Grove was now the property of an up and coming Athletics team that had won 71 games in ‘24, its highest win-total since 1914 despite finishing last in runs scored.

However, the A’s offense was surely to improve in ’25 what with the likes of young hitting stars such as Al Simmons and Max Bishop ready to see increased playing time as well as Mack’s acquiring of future Hall of Fame catcher, Mickey Cochrane, just several weeks after his purchase of Grove.

Even prior to the Cochrane acquisition that was sure to bolster the Athletics’ offense, Mack believed his team was just one pitcher away from making a serious run in 1925. Mack had been quoted as saying that “one good pitcher would put him in the pennant fight next season (61),” thus the extravagant amount paid for Grove. Moreover, the addition of Grove wouldn’t just result in more wins for the Athletics, Mack had reasoned. Mack had also envisioned Grove as being one of baseball’s biggest drawing cards, given his extraordinary ability in striking out batters, similar to the NL’s strikeout king, Dazzy Vance. “The fans being tired of this terrific slamming, what is more natural than that the pendulum should swing to pitching?” Mack asked rhetorically. “And to the average fan the pitcher who strikes them out is the most interesting man to watch (62).” Mack believed that “if Grove can find his stride…the fans will flock to the ballpark to see him turn back Ken Williams, Babe Ruth and the other homerun clouters and .300 hitters. And a few ‘flocks’ to the Athletics’ ballpark will return the hundred grand (63),” that Mack had shelled out for Grove.

However as good as Grove had been in the International League and with all his seemingly limitless potential, Grove still had to overcome his occasional bouts with wildness if he was going to fulfill the grand expectations that had been placed on him. The Allentown Pennsylvania Morning Call had made the point months before Grove’s AL debut. “One thing that may handicap Grove in the big show, however, is his wildness (64),” wrote the Morning Call. “He will be facing heavier sluggers and wiser ones. He will be forced to keep the ball out of the groove and work the corners…should the big league stickers start waiting him out he may have more trouble finding the plate (65).”

Sure enough that is exactly what happened. In the Athletics season-opener played at home versus the Boston Red Sox, Grove allowed five runs, four of which were earned, on six hits in just 3.2 innings pitched. He had walked four, hit a batter and struck out none. After two more starts in which he walked five and six hitters respectively, Grove was demoted to the bullpen on a temporary basis. He was limited to just three starts in the month of May.

Heading into his start versus the New York Yankees on May 30, Grove’s 50 walks in 58 innings pitched led the majors and his lofty 5.46 ERA was the sixth highest among starting pitchers. However, against the Yankees Grove was able to put together the best start of his brief MLB career. He allowed four earned runs on nine hits and struck out nine in a 9-7 victory. Grove was still wild as his six walks would attest but he went the full nine innings for the first complete game of his career. Grove had struggled over the final two innings but Mack had reportedly made it a point to stick with his rookie pitcher “believing that the finishing and winning of a game would set him right (66).”

Famed American League umpire and syndicated columnist, Billy Evans, had worked the May 30th Athletics/Yankees game. In one of his columns written shortly after the game Evans had evaluated Grove by way of the following:

“Grove has a great fast ball. It is the best fastball any southpaw has showed me since the days of ‘Rube’ Waddell…his curveball, while good, isn’t in a class with his fast one…Grove lacks poise. There isn’t a big league finish to some of his pitching methods but it will soon wear off. All he needs is a couple of victories to give him confidence. I would say that Grove, despite a most disappointing start, is the greatest southpaw prospect I have seen in fifteen years. I don’t think Mack paid a penny too much for him (67).”

Despite the victory over the Yankees though, Grove continued to struggle and shortly thereafter found himself back in the Athletics’ bullpen. His next start would come on June 16 versus the Cleveland Indians. Grove managed to beat the Indians despite walking eight. On June 20 he beat the St. Louis Browns, limiting the number of free passes to just two. Grove though was unable to complete either game.

On June 26 Grove faced the defending World Series Champion, Washington Senators, in front of a home crowd of nearly 30,000. On the mound for the Sens was the venerable Walter Johnson. At the time the surprising first place A’s had held just a 2.5 game lead over the Senators. The Senators though would trim the lead down to 1.5 games thanks to a seventh inning Goose Goslin 3-run homerun that powered the Sens to a 5-3 victory. Up until the Goslin homerun, Grove had pitched well. However, he unraveled in the seventh after giving up a walk and a single before the Goslin homerun, displaying that “lack of poise” that Billy Evans had referred to. Still though, Grove was able to complete the game, just his second of the year.

After three months in the majors Grove’s ERA now stood at 5.67. He had walked 85 batters and struck out 70 in 108 innings pitched. However, thanks to a much-improved Athletics offense that was third in the AL in runs scored, Grove’s won/lost record was 7-5.

Grove’s mound opponent, Herb Pennock, on the other hand was just 6-9 despite a 3.43 ERA. The New York Yankees, who had bludgeoned AL pitching ever since the arrival of Babe Ruth in 1920, were at the time, last in the AL in runs scored for a variety of reasons, most notably, Ruth’s absence from the lineup for the first two months of the season. The Yankees’ pitching though was holding its own. Led by Pennock, New York was third best in the AL in terms of run prevention.

Pennock had been acquired by the Yankees in January of 1923 from the Boston Red Sox. Pennock’s career had started slowly. It began with the Athletics in 1912 at the age of 18. Pennock had spent 4+ seasons with the A’s until being waived in June of 1915. At the time, Pennock, who possessed “a lot of pitching ability” had “shown nothing.” Reportedly “Mack had given up trying to make a pitcher out of him (68),” leading to the then 21-year old’s release. Pennock’s issue early in his career was similar to Grove’s in that Pennock had also lacked control. The Red Sox picked up Pennock for the $1,500 waiver price.

Pennock didn’t find immediate success in Boston. In fact Pennock was walking batters at a higher rate during the 1915 season with Boston than he had with the Athletics which led to his demotion to Providence of the International League. In 1916 Pennock began the season with the Red Sox but had been used sparingly. In July Pennock was once again demoted to the International League, this time to Buffalo.

The following season Pennock seemingly had made strides with improving his control. According to reports Pennock was no longer “the same skinny youngster who was trying to hit a winning stride a few seasons ago. He has put on weight and has developed a ‘good head.’ Above all he has improved his control and though he has no more stuff and curves than before he can now use all he has with confidence (68).” Limited to just five starts and 24 appearances, Pennock went 5-5 in 100+ innings pitched in 1917. His 3.31 ERA was still higher than league average; however, he was able to cut down his walk rate to 2.1/9 innings pitched, the lowest of his career up until that point.

In December of 1917 Pennock enlisted into the Navy and missed the entire 1918 major league season; although he did pitch for Navy’s baseball team. The highlight of Pennock’s career with Navy occurred on July 4, 1918. On that day Pennock started versus Army in a game played at famed Chelsea Field located in West London, England. King George V was in attendance. Pennock defeated Army 2-1.

Pennock returned to the Red Sox in 1919. The Sox, who had won the World Series in ‘18, had experienced a tumultuous 1919 season. Increased salary demands, strife among the players, an insubordinate Babe Ruth and Boston owner Harry Frazee’s ongoing war with AL President Ban Johnson, were just some of the issues the ’19 Red Sox had contended with during the season. Moreover, on the field the team had regressed, particularly the pitching.

Bullet Joe Bush, who had won 15 games for the Sox in ’18, missed almost the entire 1919 season due to a sore arm. Sad Sam Jones saw his ERA jump from 2.25 to 3.75. As a result Jones went from a 16-5 won/lost record to a miserable 12-20 record in ‘19. Carl Mays, who had won 21 games for the Sox in ’18, spent a good amount of time battling his teammates in ’19. He was subsequently traded to the Yankees that July. Moreover, the Red Sox pitching depth in 1919 wasn’t what it was the previous season. In December of 1918, believing the team had a surplus of arms, the Sox sent Dutch Leonard to New York in a six-player deal with the Yankees. In return the Sox received an ineffective Ray Caldwell. As a result, the 1919 Red Sox dropped from second in the AL in team ERA (2.21) in ‘18 to a next to last 3.30 ERA.

Herb Pennock though was one of the few pitching bright spots for the Sox. Inserted into the rotation at the end of May, Pennock went on to win 16 games. His 16-8 record, good for a .667 winning percentage far exceeded the Red Sox’ overall .482 winning percentage.

Over the next three seasons Pennock had become Boston’s most dependable starter. He led the team in wins (39), innings pitched (667) and games started (81). During that time the Red Sox had made several multi-player trades with the Yankees including the aforementioned Carl Mays deal, the selling of Babe Ruth and trades involving Waite Hoyt, Bullet Joe Bush and Joe Dugan. The Yankees usually ended up benefitting the most from these blockbuster-type trades. The Herb Pennock deal that occurred in January of ’23 was no different.

The Yankees were coming off their second consecutive AL Pennant but had been swept by the New York Giants in the 1922 World Series. In the 1921 World Series the year prior, after leading three games to two, the Yanks dropped the last three games of the series, again to the Giants. Combining the 1921 and 1922 World Series’ the Yankees had been winless in eight straight postseason games.

Believing they needed to add a left-handed starter to the rotation the Yanks traded three players plus $50,000 in exchange for Pennock. In Pennock’s first season with the Yankees, New York cruised to a third consecutive AL Pennant thanks to a superb starting rotation made up of four ex-Red Sox, including Pennock. In 1923 the Yankees’ five starting pitchers ranked in the top 25. For his part, Pennock won 19 games and lost just 6.

After the Yankees dropped their ninth straight postseason game, again versus the Giants in the ‘23 World Series, Pennock was called upon to start Game Two. He went the distance in a 4-2 victory to even the series at one and halt the Yankees postseason losing streak. In Game Four Pennock relieved Bob Shawkey to get the final four outs of the game. He was retroactively credited with the first save in Yankees postseason history. Two days later he was the winning pitcher in the Game Six clincher to give New York its first World Championship.

In 1924 the Yankees slipped to second place. Pennock though won a then career high 21 games. By season’s end Pennock had become one of baseball’s elite pitchers. His ranking among major league starters was third behind only 1924 MVP Award winners Dazzy Vance and Walter Johnson.

At the time Billy Evans stated that “Pennock is to southpaws of the American League what Walter Johnson is to the right-handers (69).” Evans described Pennock as “courageous” with a “strong heart” possessing “a will to win and an ideal temperament” as well as “intelligence.” “When a batter who has a weakness faces Pennock that individual can be prepared for the worst. Pennock simply pitches them where the batter doesn’t like ‘em…there is thought behind every ball that he pitches (70),” Evans wrote.

For the few who may have disagreed with Evans’ assessment, Pennock’s brilliant performance versus Lefty Grove and the Philadelphia Athletics on July 4, 1925 surely would have given them reason for pause. Simply put, Pennock was masterful and most of the 50,000+ New York home crowd agreed. Inning after inning Pennock was applauded by Yankee fans as he walked to the New York dugout after continually stymieing Athletics hitters over an incredible 15 innings.

Indeed. In those 15 innings pitched, Pennock allowed a grand total of just four Athletic baserunners. Moreover, Pennock had retired the A’s in order in 13 of his 15 innings of work and did not walk a batter the entire game becoming just the 10th pitcher at the time to hurl at least 15 innings in a game without issuing a free pass. So in control was Pennock that only two Athletics had made it into scoring position the entire game.

Conversely, Lefty Grove had been in and out of trouble for a good portion of the day. The Yankees were able to get a runner in scoring position in six of the game’s 15 innings. However, when Grove needed an out, he usually got one.

Grove had allowed a Yankee hitter to reach base in his first four innings of work. The bottom half of the fifth would be no different. With the game still scoreless, Grove surrendered back-to-back hits to the Yankees’ Benny Bengough and Aaron Ward to open the inning. The Ward hit had advanced Bengough to third. Following his strikeout out of Yankee shortstop, Pee-Wee Wanninger, for the first out of the inning, Grove induced a ground ball off the bat of Herb Pennock. A’s third baseman, Sammy Hale, fielded the ball and then fired to home, gunning down Bengough who was attempting to score on the play. Grove then had Joe Dugan fly out to right to end the inning.

In the bottom of the sixth Grove once again found himself in hot water. Grove surrendered a hit to the Yanks’ leadoff hitter, center fielder Earl Combs. Grove though was able to erase Combs after Babe Ruth ripped a ball that was hit directly to A’s second baseman, Jimmy Dykes. Dykes fielded the ball cleanly and then flipped it to his shortstop, Chick Galloway, forcing Combs at second. Galloway then completed the 4-6-3 double play by throwing out Ruth at first. Grove then walked Yankee left fielder, Bob Meusel. Meusel advanced to third via a Lou Gehrig single but Grove was able to get out the inning unscathed after popping up Bengough to end the frame.

In the meantime Herb Pennock was barely breaking a sweat. Heading into the top half of the seventh Pennock had retired 15 straight A’s. Leadoff hitter, Jimmy Dykes, finally ended the string after singling to center. Dykes’ hit was just Philadelphia’s second of the game. Dykes made it to third after a sacrifice and a ground out. However he was left stranded after Al Simmons lined out to right to end the inning. In the bottom-half of the seventh, Lefty Grove answered by registering his first 1-2-3 inning of the game. After seven complete the teams were deadlocked at zero.

In the bottom of the ninth with the game still scoreless, Grove displayed the poise that some believed he had lacked. Bob Meusel lined a hard hit single to center to open the inning. Meusel advanced to second by way of a Lou Gehrig sacrifice. Yankees’ manager, Miller Huggins, then sent in the dangerous right-handed hitter, Ben Paschal, to pinch-hit for Bengough. Paschal had been 4 for 11 versus Grove in ’25 including a three-run homerun in the last game they faced one another.

This time though Grove would get the better of Paschal. Paschal grounded to short for the second out of the inning but had advanced Meusel to third. Connie Mack then elected to intentionally walk Aaron Ward. Ward then stole second base. Huggins again went to his bench and sent up veteran utility man, Howie Shanks, to pinch-hit for Wanninger. Grove though blew away Shanks by striking out the 35 year-old. It was just Grove’s fourth strikeout of the game. After nine complete, the game was still tied at zero with both Pennock and Grove headed for extra innings.

In the 10th, Pennock had yet another 1-2-3 inning. In the bottom-half of the inning Grove responded with a quick inning of his own which included two more strikeouts, one of Combs, the other of the Babe. In the 11th and 12th innings, Pennock once again retired the A’s in order while Grove scattered two hits to keep the Yankees in check.

In a bizarre bottom of the 13th, after his team once again went down quietly in the top-half of the frame, Grove incredibly beat back a Yankee attack in which New York had loaded the bases with nobody out. Babe Ruth had singled to open the inning. Bob Meusel followed with a loud double to right field, advancing Ruth to third. With first base open, Grove intentionally walked Lou Gehrig to get to Yankees’ catcher, Steve O’Neill. O’Neill had replaced Bengough after the latter was lifted for a pinch-hitter back in the ninth. At the same time, Huggins replaced Ruth with a pinch-runner, that being Whitey Witt. Witt “immediately tried to steal home (71).” However, O’Neill fouled off the pitch and Witt had to return to third. Unbeknownst to Huggins though was the fact that Witt had been released by New York the night before which meant he was ineligible to play. As soon as Huggins was made aware of Witt’s release, he pulled Witt and replaced him with another pinch-runner, veteran outfielder Bobby Veach.

Grove then retired O’Neill by overmatching him with a fastball, popping him up in foul territory. Huggins kept the squeeze play on during the next two at-bats. However, the result was the same as both Aaron Ward and Ernie Johnson failed to execute. Grove had fired nothing but fastballs to both hitters. Ward popped up his attempt in foul territory while Johnson grounded out weakly to first. Incredibly Grove had managed to escape unscathed to prolong the game.

Years later Yankees’ Hall of Fame pitcher Lefty Gomez was credited for first uttering the old adage, “I’d rather be lucky than good.” Up until this point, the current Yankees’ lefty, Herb Pennock, did not need luck. He’d simply been good; very good in fact. However, in the top half of the fifteenth Pennock got lucky.

After striking out Grove to open the frame he gave up his first hit since the eighth inning when Jimmy Dykes scorched a ball “near the bleacher fence in right (72).”Bobby Veach, who had replaced Ruth in the outfield, “danced, squinted at the sun and fell to the ground trying to make a circus catch…The ball fell safe and Dykes raced all the way around to third base….Dugan (Yankee third baseman Joe Dugan) dropped the relayed throw and Dykes lammed for the plate…Jumping Joe (Dugan) made a quick recovery…because the ball made a sharp rebound to Joe (73).” Dugan then threw home to get a sliding Dykes for the second out of the inning and preserve the shutout. Pennock then had A’s third baseman, Sammy Hale, ground out 5-3 to end the inning.

The Yankees finally broke thru in the bottom of the 15th. Bobby Veach opened the inning by dumping a Grove offering into right field for a single. Meusel then sacrificed Veach to second. Oddly enough, with Lou Gehrig now at the plate, Mack had Grove pitch to Gehrig this time. Grove responded by striking out the Yankees’ first baseman. However, Steve O’Neill who had been completely overmatched by Grove in his last at-bat delivered a sharply hit ball to center to score Veach and give Pennock and the Yankees the 1-0 victory.

To say Lefty Grove suffered a tough loss would obviously be an understatement. He went 14.2 innings and scattered 14 hits. He walked five and struck out ten in the process. In doing so Grove became just the third pitcher in the live-ball era to throw at least 14.2 innings, register a Game Score of at least 87 and lose. A columnist for the Baltimore Sun summed it up perfectly when he wrote: “Grove hurled splendidly, good enough to win 99 games of a 100. But Pennock was incomparable, and this must have been that hundredth game (74).” Indeed. Nine times during his career did Grove achieve a Game Score of at least 87. He was 8-1 in those games with his only loss coming against Herb Pennock.

Pennock’s final line was 15 innings pitched; four hits, 0 runs, 0 walks and five strikeouts. In terms of Game Score (114), it was the greatest game of Pennock’s career. Combined with Grove’s 87 Game Score, the 201 total for this duel ranks as the 11th highest among the Top 100.

Interestingly Pennock and Grove would face one another just three more times in their career with Grove winning two of the three. Grove would also beat Pennock to the Hall of Fame. Grove was inducted in 1947, one year before Pennock’s induction.

Pitcher Duels Numbers 79 to 70:

Comments